The Andes Mountains are notably one of the largest and highest mountain ranges on Earth. The Andes Mountains formed while the Nazca and Antarctic plate subducted under the South American Plate creating this massive wonder of nature. The Andes Mountains spans more than 4500 miles across seven different countries, including, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina. The Andes Mountains has an average elevation of 13,000 feet high and at its tallest peak, Mount Aconcagua in Argentina, 22,841 feet high. With all the varying elevations across its span, the Andes Mountains has many different weather patterns and climates.

Currently

in the Andes Mountains

The climate in the Andes Mountains continues to change

at an alarming rate, which is directly affecting the tropical glaciers they

house. The Andes Mountains is home to more than 95% of the world’s tropical

glaciers. Snow and ice is accumulated from precipitation (water formed in the

earth’s atmosphere), aiding in the formation of the glaciers. Ablation occurs

(the natural removal of snow and ice converting into water and vapor) from the

glaciers, playing an important role in the agriculture. With the effects of

Global Warming and the impact it has on this cycle, it is dramatically changing

the climate in the Andes Mountain.

| Accumulation and Ablation of Glaciers |

The glaciers are melting at an alarming rate, 70% or 40

million natives will no longer have access to this fresh water by the year 2020

(“Water conflicts in Andes”). As temperatures rise at an average of 0.15°

C per decade, glaciers proceed to retreat. Smaller glaciers located at

altitudes below 5,400 meters with an average ice thickness of 40 meters have

lost 1.35 meters each year since 1970. These results lead scientists to believe

that these glaciers will disappear within decades (“Glacier Melting in the

Andes”).

10,000

years from now

At this rate, within 10,000 years the Andes Mountain

glaciers will have completely disappeared. Temperatures rising at elevations of

5400 meters are not able to melt the ice completely, but are able to change the

nature of the precipitation. The frost line, the maximum depth at which soil is

frozen, is retreating, limiting the snow and rain fall to higher elevation.

This limits long-lasting snow cover and prevents albedo, radiation reflected off

the surface, from protecting the glaciers surface. Glaciers at higher levels

than 5400 meters are also at risk. The radiation influx, solar radiation from

the sun absorbed and reflected by the glaciers, which is stronger in the

tropics affects these glaciers to melt at higher rates as well.

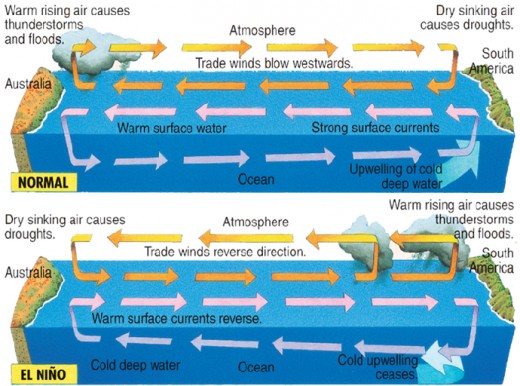

A climate pattern, categorized as El Niño that influences

weather patterns and ocean conditions has greatly influenced the change and

shrinkage of the glaciers. Having changed in frequent patterns since the

1970’s, El Niño lead the way for the dramatic disappearance of the Andes

Mountain glaciers.

|

| El Niño Event |

Some glaciers have already disappeared. In 2009, the

glacier at 5350 meter high, Chacaltaya in Bolivia melted away, once having been

one of the world’s highest ski resorts. Pico Espejo in Venezuela disappeared

earlier in 2008.

1,000,000

and 10,000,000 years from now

In 1,000,000 to 10,000,000 years from now, the native

people of the Andes Mountains will no longer exist in this area, since the

water source from the glaciers will no longer be available. As the glacier melt,

glacial erosion will occur. Glacial erosion is the carving and shaving of the

landscape beneath a moving glacier. The glacial striations left behind, will be

the only evidence that grand glaciers once covered the area. Post-glacial

rebound will occur from the weight of the melting glaciers in the Andes Mountains,

causing the land to rise. The sea level would then rise .05 meters as it

absorbs the results of this occurrence.

|

| Glacial Erosion |

The people of the Andes Mountain are not the only victims of this event, but also the ecosystem in the area. The change is happening at an alarming rate and will only continue to intensify, putting significant regions of the Andes Mountain at risk of permanent change or disappearance.

Work Cited